This is the first of three blogs in our Monumental Mammoths series about the Harwood Park playground, which features giant sculptural play elements and educational information related to Columbian mammoths, which roamed North Texas about 100,000 years ago. We recently interviewed Dr. Ron Tykoski, the Director of Paleontology and Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas, about the mammoths and their way of life. This conversation has been edited for clarity. Learn more about the playground features here, and about Harwood Park and all its amenities. Harwood Park – and the playground – is scheduled to open in spring 2023.

Tell us a little about what Downtown Dallas and the North Texas area were like 100,000 years ago, as it relates to the landscape and climate.

The landscape itself was essentially the same as you would see today, if you could remove all the buildings, parking lots, levees and dams that have covered and modified the land in just the past 150 years or so.

The wiggling, looping channel of the Trinity River meandered across a floodplain that floored the broad valley of the Trinity, but the channel and floodplain was around 50 to 75 feet higher above sea level relative to where it runs now. Numerous tributaries zigzagged their way down the gentle slope and smaller valleys to the main channel. Thick woods and brush covered the bottomlands and courses of the tributaries, while the higher ground between them was a patchy mosaic of park-like grassy savannas and trees.

Climate conditions 100,000 ago were surprisingly similar to what we have today. The planet was still in the “Ice Age,” a time of pronounced and unusually cool to cold temperatures that began around 2.6 million years ago and continues to the present day. However, conditions were not constant the entire time. Global temperatures swung back and forth from cold “glacial” to warm “interglacial” intervals many times. During cold spells, glaciers grew and spread in mountain regions, on the poles, and eventually across large parts of continents in the Northern Hemisphere. During the “interglacial” intervals, temperatures warmed, sometimes getting even warmer than modern times, and the ice sheets would rapidly melt and shrink back.

A big focus of Harwood Park will be the giant sculptural play elements modeled after the Columbian mammoths. Can you tell us about the wildlife that was present 100,000 years ago?

What lived here? Humans would not arrive in North America for another 80,000 years or so. However, let’s use our imagination a bit to set the scene. You hop into your time machine and travel back 100,000 years to see Dallas and North Texas that time. At first, you might not be that impressed as you survey the animal life, because many of the same species you see today are already here. White-tailed deer, black bear, beaver, otter, raccoons, opossums, alligators, turtles, and maybe even a puma (a.k.a. mountain lion) might make an appearance. Then though, you start to notice things that appear very out of place to a modern visitor.

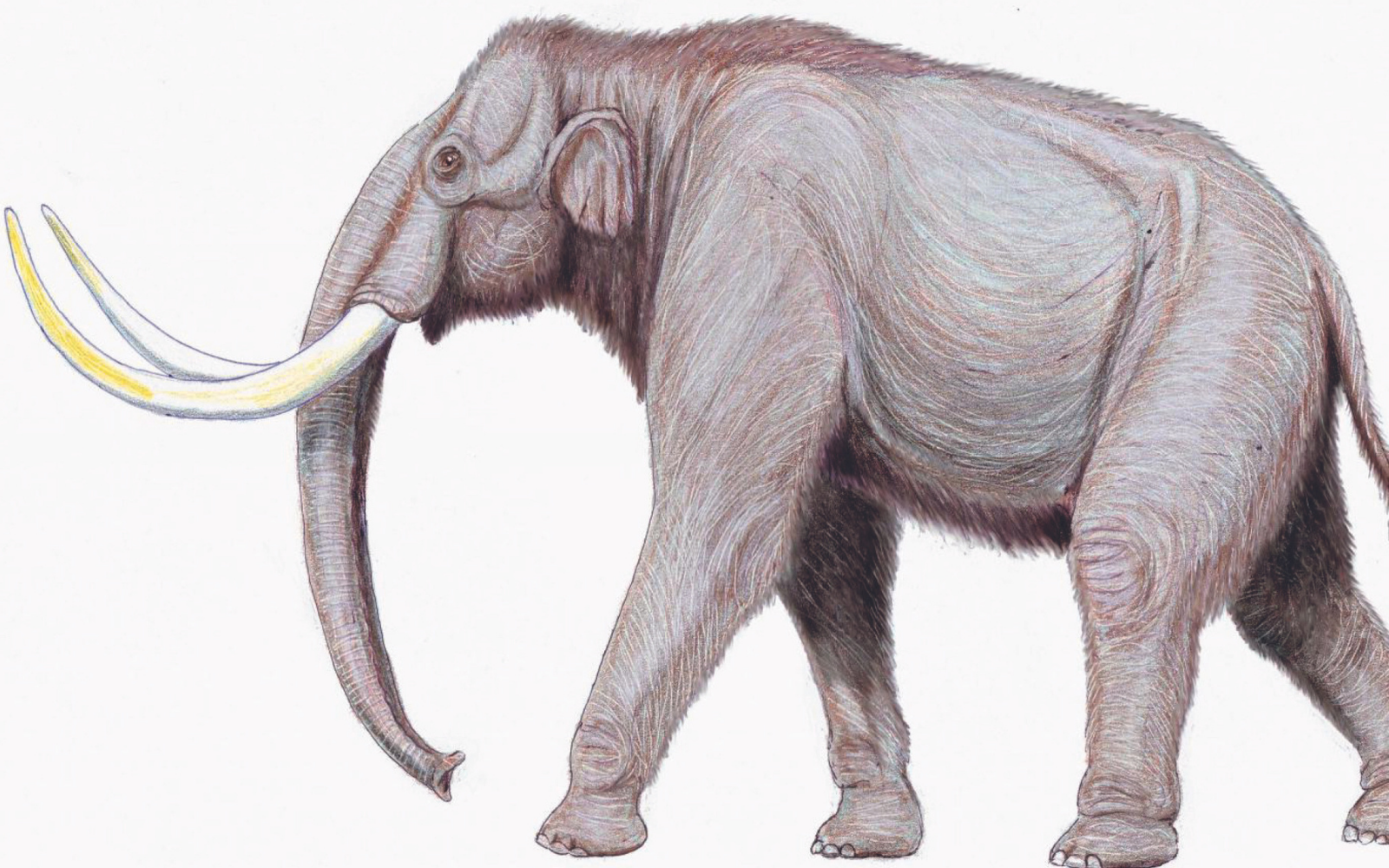

Herds of towering Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) dot the landscape, probably favoring the more open, grassy patches. Taller at the shoulder than the largest modern elephants and with immense, curling tusks that could measure 12 to 16 feet around the curl, these stately elephants graze their way across the land. They are not the only large, elephant-like animals here though. American mastodons (Mammut americanum) share the region with them. Although elephant-like in general appearance, these stockier, shorter beasts arose from a branch of the proboscidean family tree that arrived in North America a few million years earlier. The mastodons were much rarer than mammoths in Texas, apparently sticking to the wetter, brushy and wooded areas along rivers and streams.

Can you tell us a little more about the Columbian Mammoths, and how prevalent they were in the North Texas area during their time on Earth.

Columbian mammoths were long thought to have descended from the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) of Asia, after ice sheets across the northern hemisphere trapped enough of the planet’s water supply to lower sea levels by a hundred meters or more. This exposed the shallow floor of the Bering Strait, creating a land bridge connecting the continents and allowing species to swap across the region. The idea was then that descendants of the steppe mammoths evolved separately in North America, becoming the Columbian mammoth species (Mammuthus columbi). Later, yet another species, the Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) also came to North America, and for years there have been suggestions that where the two species met, hybrid offspring were produced, sometimes leading to calls for additional species to be recognized.

However, very recent DNA tests of mammoth teeth from locations in Asia tell a very different story for the origin of Columbian mammoths. According to the report, the Columbian mammoths of North America are a much more recent species formed through hybridization between Woolly mammoths and a previously unrecognized genetic line or species of mammoth! This thoroughly unexpected revelation has really stirred the pot of mammoth origins on the continent, and specialists are no doubt going to be sorting this out and reconciling the possibilities with the known fossil record for a while. Regardless of their exact origins, Columbian mammoths were simply elephants. It turns out mammoths and Asian elephants are more closely related to each other than either is to African elephants. As a result, people have often used the behaviors and social interactions of Asian elephants as modern-day models of how mammoths might have behaved and looked in the distant past.

How common were mammoths in North Texas?

Very. Mammoth fossils turn up frequently across the region, from isolated parts of their huge teeth, to chunks of tusks, to isolated bones, or even nearly complete skeletons. Take a drive down to the Waco Mammoth Site National Monument and you’ll see skeletons of a small herd that died in a steep-walled section of the Bosque River.

During the building of Dallas, multiple skulls and partial skeletons of the animals turned up in the sands and gravels of the ancient terraces of the Trinity River. The remarkable number of their remains suggests mammoths truly loved this part of Texas!

Coming up on Tuesday, August 31: Find out how the Columbian mammoths size up compared to some Downtown Dallas icons. Plus, learn more about the array of species that roamed the North Texas landscape. Learn more.

About Dr. Ron Tykoski

Dr. Ron Tykoski is the Director of Paleontology and Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas. Dr. Tykoski holds a Ph.D. in Geological Sciences from The University of Texas at Austin; a Master of Science in Geological Sciences from The University of Texas at Austin; and a Bachelor of Science in Geological Sciences from The University of Michigan – Ann Arbor. After finishing his Ph.D., he started at the Dallas Museum of Natural History as its Fossil Preparator, and continued there as the museum evolved into the current Perot Museum of Nature and Science. He’s worked on and even helped name various predatory dinosaurs, plant-eating dinosaurs, fossil crocodilians, and fossil birds over the years. In 2014, he oversaw the collection of a nearly complete female Columbian mammoth skeleton near the town of Italy, Texas, in Ellis County. He supervised the preparation of the specimen, and assisted with its installation on exhibit in the Perot Museum in 2015. The 35,000-year-old skeleton is displayed just outside the museum’s third-floor elevators.